How can human brain mappers travel more sustainably?

By Niall Duncan and Charlotte Rae

Authored on behalf of SEA-SIG, with figures from SEA-SIG’s forthcoming Symposium and publication

The problem

One of the great things about science is that it brings people together from around the world. These international connections allow people to share information and perspectives, driving knowledge forward. They also give us opportunities to meet new, interesting people and in doing so perhaps understand the world a little better. Unfortunately though, the possibility for people to come together physically from long distances also has some downsides for this planet that we all share.

As we know, Earth is facing a climate crisis. Human-induced changes in the climate are already showing their effect and are only set to get worse in the coming years. One driver of this crisis has been greenhouse gas pollution from air transport, representing around 4% of total such emissions. Even though a relatively small part of this total, we all contribute to it when we fly to connect with other scientists.

The role of scientific conferences

The majority of these science-related aviation emissions come from people attending scientific conferences, and travel to conferences is estimated to account for 91–96% of total emissions [1]. To put it in a real-life context, one person travelling from North America to Asia will produce around three tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent (CO2e) greenhouse gas emissions, which is the same amount as someone in a low-income country will generate in a decade.

However, not all conference locations contribute equally to the emissions. Looking at SEA-SIG’s modelling of previous OHBM conferences (Figure 1), we can see that travel to Hawaii in 2015 was the most polluting in terms of total CO2e emissions. Singapore in 2018 produced less CO2e overall, but tops the list in terms of emissions per person, at over five tonnes.

Figure 1. Carbon footprint of the most recent in-person OHBMs, calculated by SEA-SIG using modelling by climate scientist Dr Milan Klöwer. These data will be presented at the 2022 SEA-SIG symposium, and in a forthcoming publication.

In contrast, hosting the conference in Rome produced the least amount of CO2e per person (but note, still over three tonnes each). These figures illustrate how the CO2e outcomes for conferences are primarily based on where most OHBM members are located as this determines how far the majority of attendees must travel and by what means. This means that location of future meetings is important for minimising our carbon footprint.

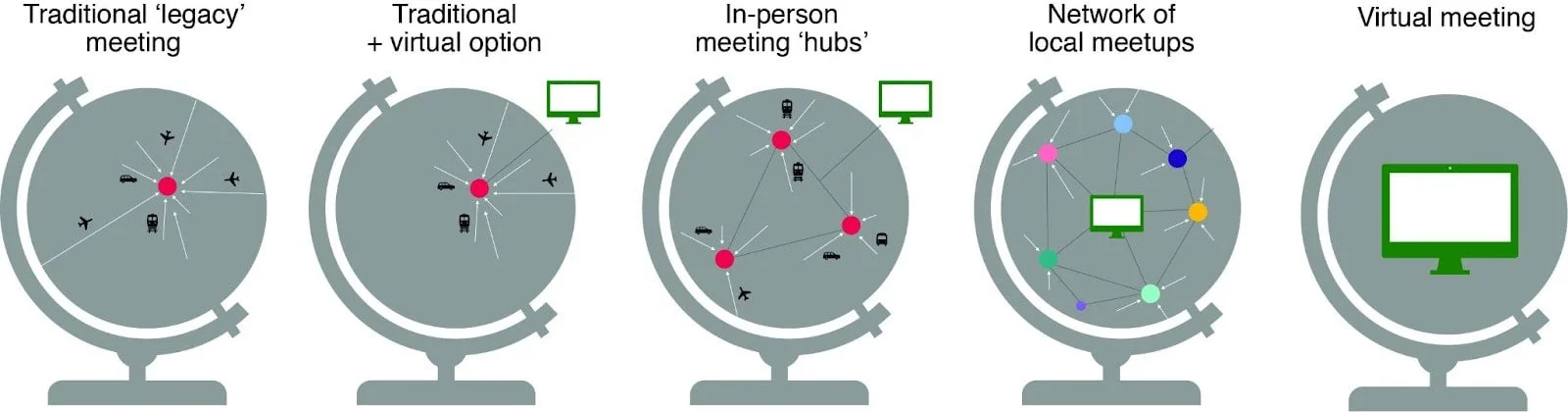

As well as meeting in person in locations that minimise the need for long-haul flights, there are lots of complementary approaches to consider. Post-Covid, we will see a transformation of traditional conference models, in which everybody comes together to meet in one place (Figure 2). As a community, we need to consider other models where that would not be a necessity. These include online, hybrid (online and in-person options), and in-person approaches such as a ‘hub’ model, in which there are multiple meeting locations, and attendees can travel to their nearest. We could also save carbon by meeting in person on a biennial basis (every other year), alternating with meeting online in between.

Figure 2. Alternative formats for scientific meetings, from traditional ‘legacy’ in person only meetings, to hybrid, hubs, local meetups, and fully virtual. Figure from Rae, C.L., Farley, M., Jeffery, K.J., & Urai, A. E. (2021). Climate crisis and ecological emergency: why they concern (neuro)scientists, and what we can do. Brain and Neuroscience Advances, 6, 1-11.

Some of these options are already available, and the adoption of online and hybrid in particular has been accelerated over the past years because of the pandemic. In SEA-SIG’s analyses of the carbon footprint of such alternative approaches, we identified the CO2e emissions produced and saved for OHBM meetings when different models are adopted (Figure 3). These figures assume that virtual conference elements produce around 1% of the CO2e emissions as in-person ones [1].

Figure 3. Comparison of how much carbon is saved by alternative meeting models in comparison to Rome 2019. These data will be presented at the 2022 SEA-SIG symposium, and in a forthcoming publication.

OHBM has already embraced a hybrid model for Glasgow 2022. If 33% of those who would otherwise fly super-long-haul (>8000km) choose to attend from home, this will save an estimated third of emissions compared to the Rome conference. This hybrid model not only saves emissions but can also open up access to people who could not previously attend the conference due to financial, political, or personal reasons. However, for hybrid OHBM meetings to be a success, it will be important for all attendees - including those coming to Glasgow - to fully engage with the online aspects being held on 7-8th June. This will be an opportunity for OHBM colleagues to get together and support our poster presenters wherever they are around the world.

Looking ahead, another option is to have regional hubs for a conference which would replace a single central location. Combined with hybrid access, this model could save an estimated 80% of greenhouse gas pollution from air travel. The pros and cons of distributed models like this will be a major topic of discussion within the scientific community in the coming years. SEA-SIG’s forthcoming publication will discuss these options and suggest a vision for how we can connect more sustainably in the coming years.

It’s not just conferences

Although conference travel accounts for the majority of science-related aviation pollution, other aspects of academia also require people to travel long distances. Giving talks at different universities is an expected part of the job, as are attending panels at grant agencies and scientific committees. Notably though, this is chiefly concentrated around a minority of senior researchers, and fortunately the trend is changing. More senior scientists are recognising the disproportionate role they play in carbon emission and are pledging to fly less or not at all for career-related events. This change is benefiting less senior scientists as well through easy access to talks and events held online, which enables them to share their work and make connections without the need of travelling. At the same time, grant agencies and scientific societies are following suit and are moving meetings and discussion online.

We need to get there somehow

Of course, meeting with our friends and colleagues in person will remain necessary (and desirable). On some occasions, we can choose to make the journey in a more sustainable manner, in particular by swapping the plane for the train, when possible.

For many journeys, this choice doesn’t add much time to the trip when travelling to airports and the time spent queuing when one gets there is taken into account. For example, someone going from Paris to Glasgow for OHBM2022 will spend around 6h15m travelling by plane, compared to around 7h30m by train. The same person going to Berlin for a meeting would spend 6h50m travelling by plane and around 8h30m by train. By taking the train to Glasgow and Berlin instead, one would save 200 and 210 kg of CO2e, respectively (calculated using the EcoPassenger tool).

Taking the train is a great option for scientists in Asia too, with high-speed rail networks available in many countries that often host large conferences, such as Japan, China, Korea, and Taiwan. To put it in perspective, travelling from Beijing to Shanghai will take about seven hours by plane but only 5h30m by train, saving 360 kg of CO2e.

One more benefit of travelling by train is that a group or friends or colleagues can travel together, having fun along the way and saving the hassle of airport queues. For OHBM2022 in Glasgow, if you’re getting there by train then you can find fellow attendees who are also going by train with the twitter hashtag #trainparty.

SEA-SIG symposium

Join us at the Glasgow 2022 SEA-SIG symposium ‘Initiatives neuroimagers can take to tackle the climate crisis’ to hear more about the carbon costs of previous OHBM meetings, and our suggestions for alternative future meeting formats that would minimise long-haul flying. Importantly, changes to how we meet will benefit both the planet and accessibility. And look out for our forthcoming publication, outlining in detail how SEA-SIG calculated the carbon footprint of previous OHBM meetings and our vision for a more sustainable conference going forwards.

References

[1] Gattrell (2022): The Carbon Costs of In-Person Versus Virtual Medical Conferences for the Pharmaceutical Industry: Lessons from the Coronavirus Pandemic. Pharmaceut Med. 2022 Apr;36(2)